If you chase salmon long enough, you start to recognize the tells. The flick of a tail just beneath the tide line. The way the water rolls when a school moves in. The streak of silver that could be anything — until it isn’t. A king digs in and bulldogs. A coho cartwheels. A sockeye flashes once and vanishes. Each has its own rhythm, its own signature in the water.

Knowing what you’ve hooked isn’t just a point of pride. It’s a sign of respect — for the fish, the run, the system that keeps them coming. And sometimes, it’s the difference between a legal catch and quick release.

There are six species most anglers run into. Five Pacifics — Oncorhynchus — and one Atlantic, Salmo salar. You can tell them apart if you know where to look. The color. The spots. The gums. The attitude.

Chinook Salmon (King Salmon)

When a Chinook eats, it feels like someone dropped an anchor on your line. Big shoulders. Deep power. None of the flashy jumps you get from coho. Just raw, unrelenting weight. In the ocean, they carry a blue-green back and silver sides, with black spots scattered across both lobes of the tail. But the easiest way to know you’re holding a king? Check the gums. Jet black. Always. That’s their calling card.

Freshwater changes them completely. Shine fades. Backs darken to olive or maroon. Males grow that hooked jaw — the kype — and bulk up for the upstream grind. They look less like ocean fish and more like river monsters. Chinook roam from California to Alaska, even across the Pacific Rim to Japan. Big rivers. Heavy current. That’s their world. They average 10 to 50 pounds, but plenty are even bigger. Hook one like that, and you’ll never mistake it for anything else.

- World Record: 97 pounds, 4 ounces, caught in the Kenai River

Coho Salmon (Silver Salmon)

Coho are the acrobats. They ride the drag they way kings do. Instead, they flip, twist and launch themselves out of the water in a flash of silver. Saltwater coho are bright, almost reflective, with small black spots only on the upper tail and back. White gums are a dead giveaway if you’re unsure.

In the river, males darken, sides turning deep crimson, back blackening, jaw curving into the kype. Females are subtler but just as determined. Most coho fall between 6 and 12 pounds, though northern monsters occasionally push 20. Their runs overlap with Chinook, but they favor smaller tributaries, clearer water, and aggressive feeding zones.

- World Record: 33 pounds, 3 ounces, caught in the Salmon River

Sockeye Salmon (Red Salmon)

Sockeye are firecrackers in freshwater. In the ocean, they look unassuming — slender, silvery, unspotted. But upriver, they erupt into color. Males glow fire-engine red with bright green heads. Females go crimson but stay smoother and less flashy. One second you think you’re seeing a silver dart; the next, it’s impossible to mistake.

They eat mostly plankton, which gives their flesh that deep red, almost buttery texture. Four to 10 pounds is standard, but size isn’t the point — visibility is. You can find them from the Columbia River northward through Alaska, with Bristol Bay being the epicenter of the world’s most prolific sockeye runs.

- World Record: 15 pounds, 3 ounces, caught in the Kenai River

Chum Salmon (Dog Salmon)

Chum salmon get a bad rap among trophy hunters, but anyone who’s tangled with one knows they can pull like freight trains. In their ocean form, they look a lot like sockeye — silvery and clean, without spots on the back or tail. But once they start their spawning run, they become something altogether different. Males flare with bold, vertical bands of olive, purple, and maroon down their sides, earning them the nickname “tiger salmon.” Add in the sharp canine teeth that protrude during spawning, and it’s easy to see where the “dog salmon” name comes from.

Chum average between 8 and 15 pounds, though some push past 20. They’re widely distributed, running from Oregon all the way to the Arctic, and their adaptability to both coastal and interior rivers makes them one of the most widespread salmon in the Pacific. They may not win beauty contests, but when they’re fresh out of the salt, few salmon fight harder.

- World Record: 35 pounds, caught in British Columbia

Pink Salmon (Humpy Salmon)

Pinks are the smallest of the Pacific salmon, but what they lack in size, they make up for in sheer abundance. They’re also unique in that they have a strict two-year life cycle, meaning odd- and even-year runs are genetically distinct populations. In the ocean, pinks are bright silver with large, oval black spots scattered across the back and both lobes of the tail.

When males move into freshwater, they develop the characteristic hump along their back — hence the nickname “humpy.” Their color shifts to grayish-brown, and their jaws hook into that familiar salmon kype. Females stay more streamlined, maintaining more silver through the run. Most pinks weigh 3 to 5 pounds, though the occasional 10-pounder shows up to keep things interesting. You’ll find them from Puget Sound to Alaska and across to Russia, often thick enough in the rivers to turn the water alive with movement.

- World Record: 14 pounds, 13 ounces, caught in Monroe, Washington

Atlantic Salmon

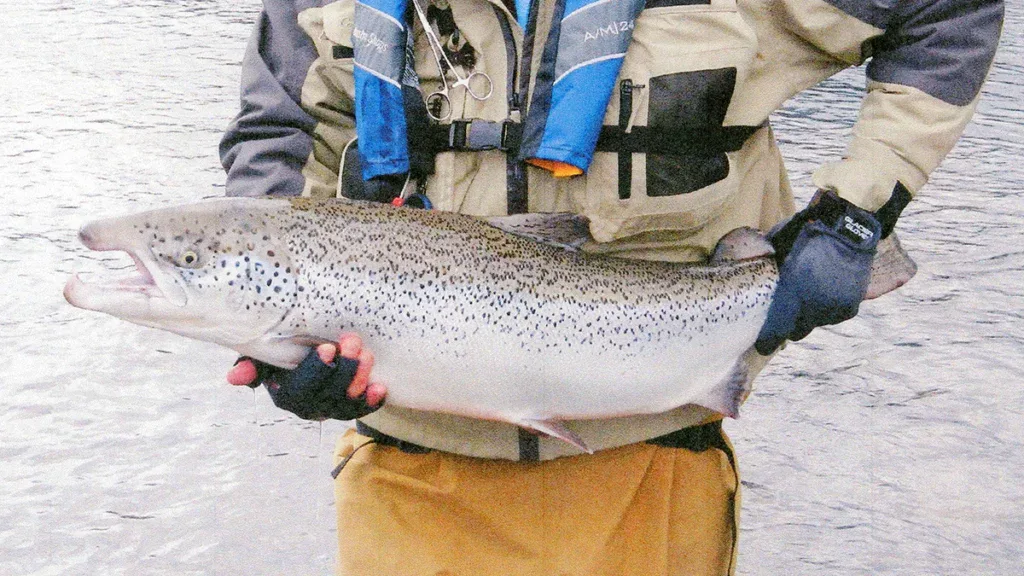

Then there’s the outlier: the Atlantic salmon. Unlike their Pacific cousins, Atlantics are capable of surviving the spawning process and returning to sea to do it all over again. In the salt, they’re bright silver with small black spots on the upper body and gill covers, and their tail is slightly forked with no spotting. During the spawn, males turn bronze or reddish-brown, their backs darken, and they develop a modest kype — not as pronounced as the Pacific fish, but noticeable all the same.

Native to the rivers of North Atlantic, these fish once thrived on both sides of the ocean — from Maine to northern Europe — but habitat loss and overfishing have taken their toll. Today, most Atlantic salmon fishing in North America happens in stocked or restored populations, including the Great Lakes and parts of coastal Canada.

- World Record: 79 pounds, 2 ounces, caught in the Tana River, Norway