Targeting suspended bass can be very difficult and was nearly impossible until recent advancements in marine electronics. During certain times of the year, however, these suspended fish can be the biggest bass in a fishery. Balls of bait move up and down in the water column in the fall and the bass stay right on their tails. But if you want to catch them, you’ve got to be able to find them.

Professional angler Russ Lane prefers to target these fish because he knows they’re less pressured than most. But locating them is easier said than done if you’re going on the search relatively blind. Many anglers don’t even bother with suspended fish and only fish for them after they’ve accidentally trolled or idled over top of them. You need a specific tool for this style of fishing. And for Lane, that tool is his Garmin LiveScope.

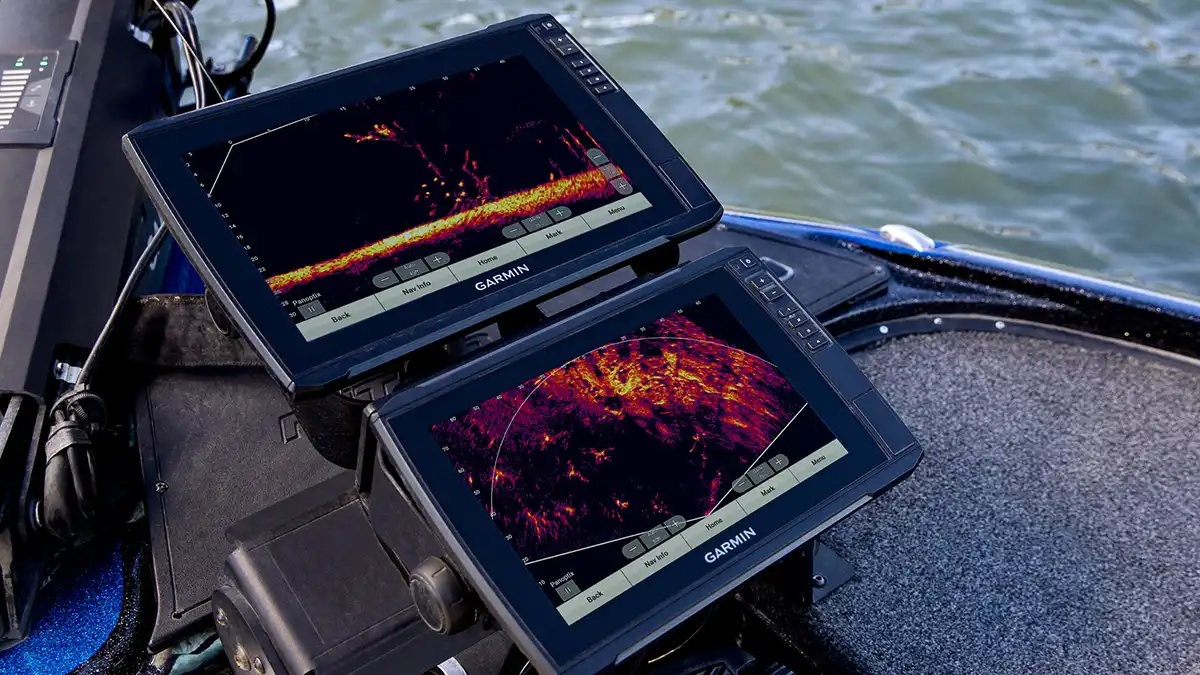

At its rudimentary level, a LiveScope transducer sends out a signal that returns immediate information in order to produce a live image on the Garmin unit aboard the boat. The transducer is mounted to the trolling motor which allows an angler to pan around 360 degrees while surveying the water below.

“What I’ve learned with LiveScope is that suspended fish swim around like fish in an aquarium,” Lane said. “They don’t like to be under boats, even if they’re in 30 feet of water. So if you run over one, they know you’re there and they’ll often swim off and you don’t know which direction they went. But now, you can take LiveScope and chase them. You can literally chase them across the lake. That doesn’t necessarily mean you’re going to catch all of them. But a lot of them you can catch.”

The importance of LiveScope

It’s been amazing to see how far technology has come in the fishing industry. Although it won’t make the fish jump into your boat, success stories of LiveScope are being told throughout the entire country. Now that he has experienced it, Lane can’t imagine fishing without it.

“I caught some on a jerkbait earlier in the year at Falls Lake in the BPT where I made a Top 10,” Lane said. “The week before, I caught a bunch of spotted bass back home in Alabama fishing in the same color water, set up on the same kind of little rocky deals, working the bait really fast.

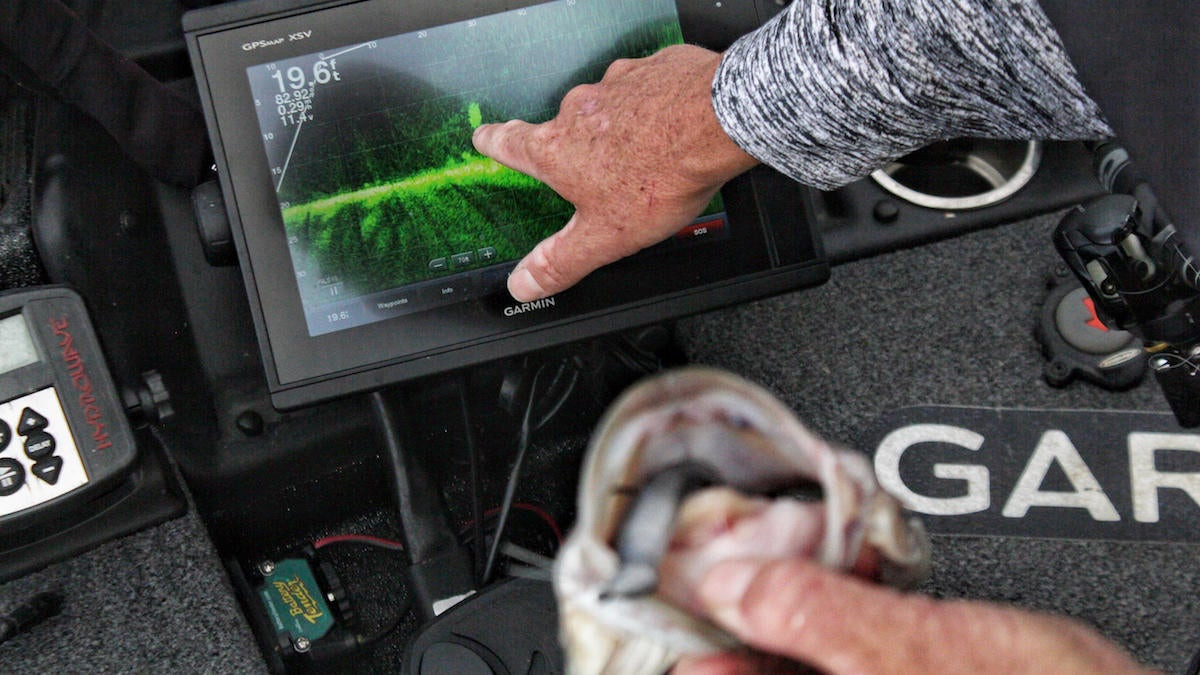

“But the fish at Falls Lake wouldn’t touch my jerkbait or respond to it on LiveScope working it fast. So I realized after watching them that I had to slow it down and just barely tap it. Seeing how they would and wouldn’t react allowed me to dial in on what it took to make them bite, where in the past I would have just fished through there the way I had back home the week before and left without a bite.”

If you’ve been on the fence about utilizing this new technology, you should get in the boat with someone who has it. After one trip, you’ll be wondering what you’ve been missing out on this whole time.

How to determine where to look

When he first puts his boat into a lake, Lane immediately begins to gather information that will shorten his learning curve. The two primary things he looks for throughout the fall months are forage species and water clarity.

“Shad and herring kind of behave similarly,” Lane said. “But shad will do a few different things, such as suspend in the water column. Brightness and water clarity seem to have an effect on how deep they’ll suspend, how much they move around and how tightly they ball up. And of course, some of the shad will migrate to the backs of creeks where there’s sandy or silty sediment in the water.

“To my knowledge, herring don’t do that. They tend to just school up and roam. It also seems like there are fewer herring in a school and they don’t relate as tightly to each other as shad do.”

The key difference, however, revolves around the gypsy-like behavior of herring when they’re suspended in deep water. While the shad seem to be a little more sedentary in this situation, the pelagic nature of the herring leads to much more roaming, making them more difficult to pinpoint with traditional sonar.

“The one difference I’ve really noticed in shad and herring is when they’re suspended in deep, clear water,” Lane said. “There, the herring move around a whole lot more. The herring are way more pelagic than shad seem to be. And the herring are less reliable each day. Any type of change in the weather or the wind seems to change their behavior quickly. They’re more likely to relocate when conditions change.”

How to target a suspended fish

The emergence of Garmin LiveScope has shown Lane the sheer importance of stealth when targeting these suspended bass. A number of things-closing a boat lid, trolling motor noise, footsteps or even your boat’s shadow-will spook suspended bass. Fortunately, this new technology allows the angler to stay far away from the fish.

“Fishing for these suspended bass is like stalk-hunting a deer,” Lane said. “You creep around and the goal is to see the deer before the deer sees you, smells you or feels you. From what I’ve seen and learned about suspended fish from LiveScope, you increase your odds tremendously by being able to see that fish and cast to them from 50 feet away instead of dropping vertically on them. You catch a bunch more.”

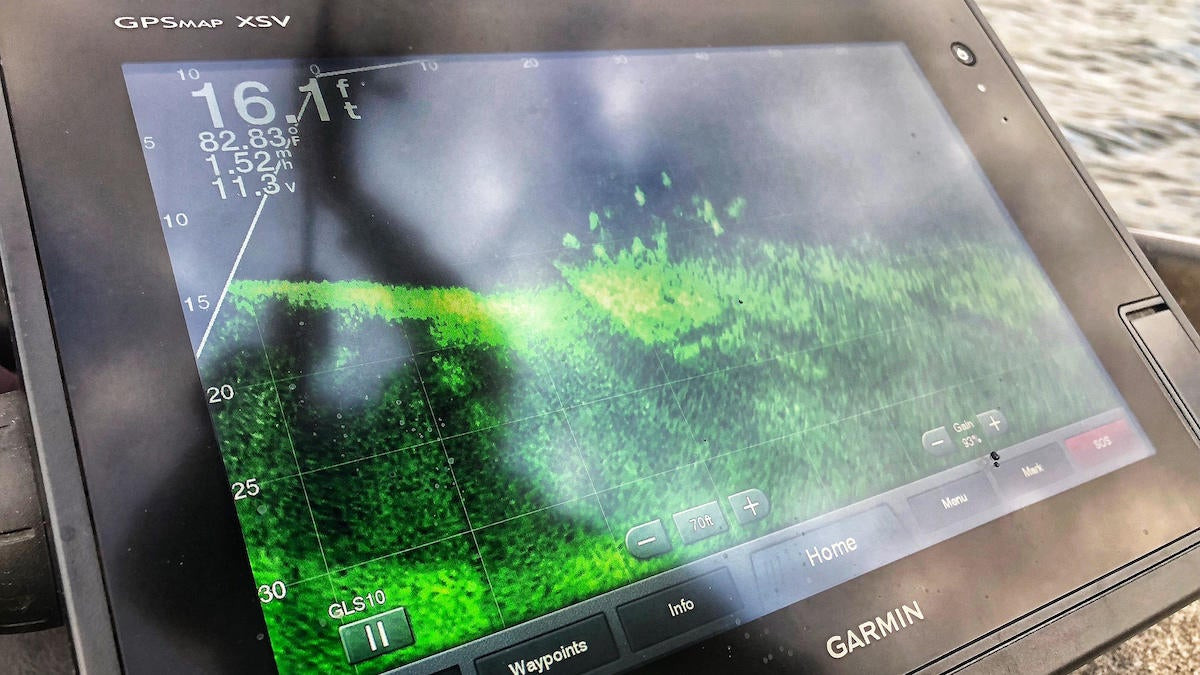

“If you have your LiveScope set at a range of 70 feet, your image is going to be clearer the closer the fish is to your transducer. But if you see something way out that could be a fish, start creeping towards it until the image becomes clearer. Now you’ve got him. You just have to make the cast.”

Although it may seem elementary, it’s important to be able to range your casts accurately. It’s not as easy as it sounds to guess how long a cast needs to be in order to reach fish at different distances. This is a key skill to maximizing your success with LiveScope.

“If a fish is 50 feet away on your graph, to make that cast you have to know what 50 feet is on the surface,” Lane said. “Then, you pan back and forth until you get the brightest, clearest image of that fish. If you scan too far to the left or right, you’re going to lose part of that image. But if you’ve got him squared up and your transducer is pointed right at him, you have the strongest return you’re going to get and you know that’s exactly where he is. When he’s as clear as you can make him be, you’ve got him.”

How to catch a suspended fish

Lane primarily uses two swimbaits to target suspended bass, the 4 1/2-inch Big Bite Baits BB Kicker on a 1/2 or 3/4-ounce Buckeye Weedless J-Will Swimbait Head and the 3 1/2-inch Big Bite Baits Finesse Swimmer on a 3/8-ounce Buckeye Weedless J-Will Swimbait Head.

“Whether I’m fishing around herring or shad, I like to start off with that BB Kicker because the tail has such a wide kick and it moves a lot of water. This actually makes it much easier to see the bait on LiveScope. It’s also easier to cover water with that bait and the tail attracts fish from a distance a little better.

“When I make a cast with one of these swimbaits, I’ll start by counting the bait down and then use a slow and steady retrieve to intersect the fish. If I make a good cast, I can actually see my bait and the fish the whole time. I’m trying to get a reaction on that first cast and whether I get a reaction or not, it tells me what to do the next cast.”

Although the technology is nothing short of remarkable, it’s important to remember that a bass is still a wild animal. You might be able to see a few right in front of your boat, but that doesn’t always mean they’re going to bite whatever you throw at them.

“If the fish doesn’t react right away, sometimes I can hop the bait up and make the fish react,” Lane said. “Sometimes I can get three or four fish chasing it up and following it down but they won’t quite eat it. I can see all of this on the LiveScope.

“It’s like messing with a bed fish and you get him spinning around. You know he’s about to bite it. It’s the same kind of deal if you can get those fish that are following the bait to all start spinning around and doing figure eights on the bait. When you get them excited like that, you know you’re getting closer to getting one to bite. And there’s no way to interact with suspended fish like that on the retrieve or judge their reactions without LiveScope.”

Whenever the swimbaits fail to produce bites, Lane has found a much more finesse approach that offers a more subtle profile and action. This can appeal to lethargic bass when they’re in a neutral state.

“It’s kind of like a Damiki rig but not exactly,” Lane said. “I rig a 3 3/4-inch Big Bite Baits Jointed Jerk Minnow on a 3/16-ounce Buckeye G-Man Finesse Swimbait Jighead. I’ll cast it to them when I see ’em on the LiveScope and just tight-line it and make it intersect the fish. You can follow your bait while you’re doing this but what you’re actually seeing on the LiveScope isn’t your bait, it’s the disturbance your bait is making the water. So with small stuff like this, sometimes you’ll lose sight of it and if you want to find your bait you can crank it real fast and you’ll see it disturb that water and then slow it back down if you need to to finish the presentation.”

Dialing in your LiveScope

The more you tinker with your LiveScope settings, the more you’re going to learn about which things work in certain situations. It’s essential to gain a solid understanding of the settings because, as with any marine electronics, there’s never a “perfect” setting that works for every single circumstance.

“There’s not really a perfect group of settings,” Lane said. “You just kind of have to play with it every day. People’s eyes are different. I see the green emerald color way better. That just pops for me. But I hear a lot of people talk about the copper and amber colors, too.

“Then you just have to play with the brightness and contrast to get it right for your eyes. I don’t use it on auto-depth or auto-range either because I want to consistently know what I’m looking at without having to look at the numbers. It’s better to me if it’s not constantly bouncing around. I always set my depth manually to be three or four feet deeper than the water I’m in. If I move shallower or deeper, I just bend over and adjust it a little. I always keep my outward range on 70 feet because I was a baseball pitcher and know exactly what 60 feet, 6 inches looks like.”

Fixing your outward range to something constant is quite important when trying to quickly identify what you’re seeing. There is a grid system on the screen of Lane’s Garmin that not only helps him quickly calculate the distance of a fish, but also how big it is.

“You can calculate how many real inches every box of the grid on your graph represents based on your outward range,” Lane said. “So if you see a fish sitting in a box, you can tell about how long it is. I mean you can tell if it’s a 3-inch bream, an 18-inch bass or a 3-foot gar just by looking at that grid. But if your range settings are on auto, then that scale is constantly changing.”